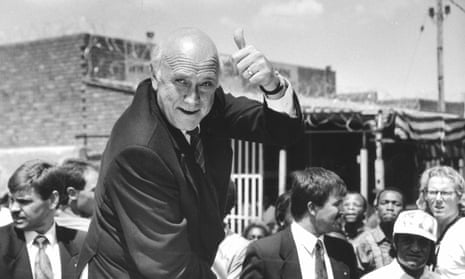

Frederik Willem – FW – de Klerk, who has died aged 85, was the last president of South Africa under apartheid. He was often compared with Mikhail Gorbachev, the last leader of the Soviet Union, for his work in consigning a bankrupt and reviled regime to oblivion.

When De Klerk succeeded PW Botha in 1989, he oversaw an event no less unexpected than the collapse of Soviet communism was when Gorbachev came to power in 1985. His stunning act of realpolitik in announcing sweeping political reform, including the release of his eventual successor, Nelson Mandela, was the grand gesture that saved his country, and in 1993 they shared the Nobel peace prize. The following year Mandela became the country’s first democratically elected leader.

Fears of uncontrollable bloodshed and civil war had proved unfounded as De Klerk led a skilful, strategic withdrawal by the white, Afrikaans-speaking inventors of apartheid, the National party, in power since 1948. Very few observers of De Klerk’s presidential term expected to see the end of apartheid in their lifetimes. Almost nobody, not even his NP colleagues, appreciated that there was more to this machine politician than affability and adroitness in debate.

Anglophones as well as Afrikaners wanted him to preserve white supremacy, while the black African majority wanted, but could hardly have expected, him to run up a white flag. South Africa got a radical pragmatist with a talent for negotiation who set about the tortuous preparation for an orderly transfer of power. Foreigners made the same mistake about De Klerk as they had about his two predecessors, Botha and John Vorster: because he, too, spoke English like a steamroller he could only be dimwitted. But it was simply not his mother tongue.

Born in Johannesburg, FW was the son of Hendrina (nee Coetzer) and Jan (Johannes) de Klerk, a teacher. His father was also Transvaal general secretary of the NP and a member of the province’s parliament and cabinet, until appointed to the senate, the upper house of the old white central parliament in Cape Town, as national minister of labour and public works.

The young De Klerk was thus steeped in Afrikaner politics from childhood. Already an NP activist, he left Monument high school in Krugersdorp to study law at Potchefstroom University, graduating in 1958.

He became a qualified attorney in private practice at Vereeniging, Transvaal (now Gauteng), in 1961, and a decade later was chosen at short notice as parliamentary candidate for Vereeniging, and elected in November 1972. After hard work on committees he became the NP information officer for Transvaal, the constitutionally federal party’s dominant province. When in 1978 Botha succeeded Vorster he promoted De Klerk to the cabinet, where he held six posts in succession over 11 years.

But his key appointment was not in Botha’s gift: he was elected Transvaal leader of the NP in 1982. Botha was an anomaly, having risen to supreme office via the Cape provincial leadership largely because Vorster, disgraced over the “Muldergate” secret slush-fund scandal, had been a Transvaaler.

This promotion made the less than colourful De Klerk the heir apparent to Botha as the next “chief leader” of the NP and state president, into which office the premiership was absorbed under Botha’s constitutional changes, which came into effect in 1984.

Meanwhile Botha was ineptly seeking to break out of South Africa’s increasing isolation. But when US banks, prompted by superbly organised African-American lobbying, halted investment in South Africa and started a stampede, apartheid’s number was up. While Margaret Thatcher railed against sanctions as “immoral” and Ronald Reagan’s US administration secretly backed South Africa’s disastrous intervention in the Angolan civil war, sanctions finally worked. The currency shrivelled, the economy reeled and internal unrest mounted, provoking a prolonged and bloody state of emergency throughout the late 1980s.

The bellicose Botha was not the man to achieve a fair settlement with the turbulent black majority. The best he could manage in his constitutional changes of 1984 was to give “coloured” (mixed-race) and ethnic-Indian minorities separate chambers in parliament, while the black majority were left to exercise their “rights” through tribal homelands that occupied just 13% of South Africa’s worst land, and in which millions of them did not even live. De Klerk assisted in this last realignment of partitions until apartheid was fatally holed by an economic iceberg.

The crash came in 1989. A fissure had opened in the NP, with the diehards defecting to the Conservative party, founded in 1982. Botha resigned as NP leader in January 1989 after a stroke. De Klerk was elected leader in his place, but Botha clung to the presidency – only to resign in a huff that August when De Klerk dared to go to Zambia for talks with President Kenneth Kaunda without his permission. De Klerk was appointed head of state and government in September by an electoral college formed from the three racial chambers of parliament.

He began to unravel apartheid by organising the repeal of one racist law after another, reining in the rampant security apparatus built up by Vorster and Botha and finally, in February 1990, releasing Nelson Mandela. The magic of his name had survived 26 years in jail and even the Botha regime had been driven into secret, though abortive, contacts with him. De Klerk realised that no settlement could be achieved unless he was freed, and years of fraught negotiation between the NP and the African National Congress ensued, leading to the first election by universal franchise in 1994.

Mandela was duly sworn in as the country’s first black president, while De Klerk became vice-president in the transitional government. He would have been well advised to bow out gracefully at once, with the Nobel peace prize shared with his successor, when the worldwide esteem he had earned by his statesmanship was at its height.

But, booed by leftwingers at the Oslo prize ceremony and blasted by white rightwingers at home, De Klerk soldiered on from 1994 to 1996 as Mandela’s increasingly embittered deputy. The two men exchanged insults in public, belying the handshakes and fine words at the handover.

De Klerk resigned as NP leader and left politics in 1997 to write his memoirs. He had already withdrawn the NP from the government of national unity in 1996, sidelining it after 48 years in power. The rump was reconstituted as the New NP, and De Klerk left it in 2004 when it merged with the ANC.

As the remarkable work of Archbishop Desmond Tutu’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission continued meanwhile, the horrific measures taken by successive NP leaders to preserve white domination were exposed – clearly enough to lead to the inescapable conclusion that De Klerk, as a cabinet minister, must have been aware of them, even though Botha made the big decisions.

De Klerk’s memoirs, The Last Trek: A New Beginning (1999) were a classic politician’s apologia, rejecting blame for the actions of the security forces, which he had been obliged to appease even as he negotiated power away. By then he had instituted the De Klerk Foundation, to “work for peace in multicommunity societies”.

In 1969 he married Marike Willemse, and they had three children, Susan, Jan and Willem. After their divorce in 1998, De Klerk married Elita Georgiades. Marike was killed during a robbery in 2001; Willem died in 2020. De Klerk is survived by Elita, Susan and Jan.

Coupling the names of De Klerk and Mandela, as the Nobel committee did, may seem like placing a garden gnome alongside a Michelangelo statue. Yet the peaceful triumph of the latter would not have been possible without the pragmatic statesmanship of the former, however grudging. White diehards condemned De Klerk as a Judas. The analogy is totally false.

De Klerk may have been driven by historic necessity, but unlike his predecessors he recognised it, and displayed moral courage in acting on it, saving untold South African lives in the process.

Frederik Willem de Klerk, politician, born 18 March 1936; died 11 November 2021

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion